Upcoming Events

Holiday Party for Clients, Residents & Tenants

Thursday, December 5, 2019

5:30 – 8:00 pm

Kohler Banquet Center –

Lincoln Room

4572 Presidential Way

Kettering, Ohio

For tickets please contact Kathy Nickell at knickell@ placesinc.org or 937-461-4300.

Mental Illness and the Homeless

According to a 2018 assessment by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), 552,830 people were homeless on a given night in the United States. At a minimum, 138,207 (25%) of these people were seriously mentally ill and 248,773 (45%) had a mental illness.

Affective disorders (e.g., depression and bipolar disorder), schizophrenia, anxiety disorders and substance abuse disorders are among the most common types of mental illness in the homeless population, at a much higher incidence rate than the general population.

What Is a Brain Health Disorder?

A condition that impacts someone’s mood, thinking or behavior, often leading to their having difficulty in one, or all, of the major life areas (i.e., social, physical, emotional, intellectual and spiritual). Examples include anxiety disorders (e.g., post- traumatic stress disorder, obsessive- compulsive disorders); mood disorders (e.g., depression, bi-polar disorder); schizophrenic disorders; and substance use disorders.

Mental Illness and the Homeless

According to a 2018 assessment by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), 552,830 people were homeless on a given night in the United States. At a minimum, 138,207 (25%) of these people were seriously mentally ill and 248,773 (45%) had a mental illness.

Affective disorders (e.g., depression and bipolar disorder), schizophrenia, anxiety disorders and substance abuse disorders are among the most common types of mental illness in the homeless population, at a much higher incidence rate than the general population.

De-stigmatizing Mental Illness in Books and Movies

The sensitive, accurate portrayal of characters with behavioral health issues in movies and books has gone a long way towards changing public opinion. Here are some popular examples that helped open minds and reduce the stigma of mental illness.

» A Beautiful Mind (2001) – Russell Crowe plays a math genius who lives with schizophrenia.

» Donnie Darko (2001) – A cult class sci-fi film that deals with paranoid schizophrenia.

» Matchstick Men (2003) – Nicolas Cage is a con artist with obsessive-compulsive disorder, agoraphobia and panic attacks.

» Black Swan (2010) – Natalie Portman plays a ballerina whose pressure for perfection may have led to psychosis.

» It’s Kind Of A Funny Story (2010) – Keir Gilchrist plays a teenager who checks himself into a psychiatric ward because of his depression and suicidal thoughts.

» Silver Linings Playbook (2012) – Untreated symptoms of bipolar disorder cause Bradley Cooper’s character to lose his wife and job, when he meets Jennifer Lawrence in a ballroom dancing class.

»

The Perks of Being A Wallflower (2012) – This coming-of-age movie featuring Logan Lerman, Emma Watson and Ezra Miller shows the highs and lows of growing up with mental illness.

» The Skeleton Twins (2014) – A brother and sister suffering from depression meet as a consequence of their mutual suicide attempts.

» Infinitely Polar Bear (2015) – Mark Ruffalo plays a father with bipolar disorder who becomes sole caregiver of his children.

» Welcome To Me (2015) – Kristen Wiig plays a lottery winner who goes off her medication for borderline personality disorder and hosts her own talk show.

» Inside Out (2015) – Animated feature that creates characters out of a young girl’s anger, fear, sadness, joy and disgust when she grapples with a family move.

» To The Bone (2017) – Starring Keanu Reeves and Lily Collins, this is a realistic depiction of a 20-year-old college dropout’s struggle with anorexia.

» Manchester By The Sea (2017) – Casey Affleck’s character comes to grip with depression and substance abuse in the course of caring for his nephew.

Sources: National Alliance on Mental Illness, TheMighty.com.

Opiate Use in the U.S.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) released these statistics on opioid use in the United States:

» From 1999 to 2017, more than 700,000 people have died from a drug overdose.

» Around 68% of overdose deaths in 2017 involved an opioid, which was 6 times higher than in 1999.

» On average, 130 Americans die every day from an opioid overdose.

Each year, PLACES provides behavioral healthcare to nearly 300 adults, about two-thirds of whom are homeless. The majority have been diagnosed with a serious and persistent brain health disorder. In this issue, we take a close look at stigmas about those disorders and what is being done to create a more open-minded environment.

By Roy Craig, Executive Director, and Brian Wlodarczyk, Clinical Services Director

One of the most intransigent barriers to mental health treatment is stigma: direct or indirect discrimination simply because a person has a health condition that, through no personal fault of their own, impacts their mood, thinking and behavior. While people diagnosed with most illnesses are not treated this way (think cancer or diabetes), why do we stigmatize those with brain health disorders? The world finds ways to discount, discredit and disgrace the mentally ill at many levels: systemic, social and personal.

One of the first places to look is how federal and state laws fund treatment of people diagnosed with these brain disorders. There are major funding differences between physical and behavioral health diseases in the Medicaid and Medicare systems, in many healthcare insurance plans, and in various state laws and regulations that guide disparate funding. Further evidence is found in areas such as inpatient rehabilitation stays. Just as for many other illnesses, sometimes a hospital stay is indicated to help alleviate symptoms and treat the condition. As former Congressman Pat Kennedy said in USA Today, “Mental health is a separate but unequal system.” He added, “We have a wasteland of people who have died and been disabled because of inadequate care.”

Our summer 2018 newsletter provided a detailed outline of funding decisions for mental health treatment made by the federal government in the 1960s. That’s essentially when federal funding was greatly reduced and state and local governments were expected to take on responsibility for hospitalizations, treatment, medication and supportive housing. The end result was, and still remains, severe cuts in mental health treatment dollars and the steady reduction in available residential options for behavioral healthcare. Imagine the uproar if, rather than reducing funding for behavioral health, similar funding cuts were made to the treatment of cancer or heart disease.

Social stigma can impact the ability and willingness of physicians and other health care workers to identify brain health disorders. It often keeps people from admitting to or discussing the impact of brain disorders on their family and its individual members. Because brain health issues are shrouded in this stigma it is difficult for social networks of those with brain health issues (friends, family, employers, etc.) to understand the challenges caused by these diseases. The issues can be made worse by the increased probability of being bullied, harassed and victims of violence.

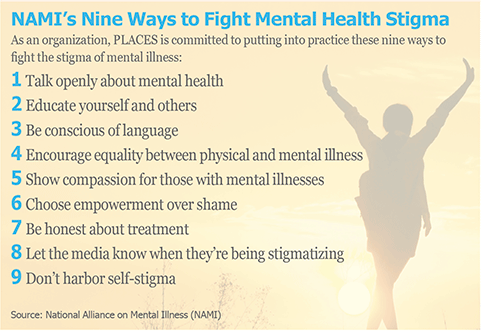

According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), one frequent result of stigma is for individuals to be ashamed for something that is out of their control. Far too often the stigma negatively impacts an individual’s educational, vocational, social and family-relational experiences as well as one’s ability to maintain safe, affordable and stable housing. However, personal stigma may perhaps be the most damaging when it prevents individuals from seeking help.

Given the alarming increase in the occurrence of mass shootings, including the recent horrific incident in our community, it is important to mention what we know about the connection between mental illness and violence. In general, the research indicates that people with serious mental illnesses are no more likely to commit heinous violence than the general population. However, there may be an increase in the propensity for violence if the mental illness goes untreated.

At PLACES, we believe it is important to be a strong, clear voice to help normalize (de-stigmatize) brain disorders. One way is by advocating for more funding to support prevention efforts and treatment. Another way PLACES supports removing stigma is to challenge people about their attitudes and the language they use to refer to people who live with brain health issues. Every person who has been diagnosed is an individual with a legacy and a story, and should be respected as such.

We spend considerable time at PLACES on training staff that our work to provide housing and behavior healthcare services should be guided by the values of respect, dignity and compassion. These values are the basis of all human relationships, including therapeutic ones. This culture is so important to our company that a significant part of staff performance evaluation involves how well these values are a part of their daily work.

Meet Our New Clinical Services Coordinator

Amber Howard joined PLACES in August as its Clinical Services Coordinator, reporting to clinical director Brian Wlodarczyk. Amber is a Licensed Professional Clinical Counselor with Supervisory Designation (LPCC-S) who earned her master’s degree from Wright State University in Counseling, with a focus on Marriage and Family Counseling.

Amber graduated with bachelor’s degrees in psychology and Spanish from Ohio University and studied abroad for a quarter in Pamplona, Spain.

Amber has worked in outpatient settings with children, adolescents, families and adults with a variety of mental health, physical and environmental barriers. Some of her previous roles include case manager and counselor in community mental health settings, counselor and then director at an agency that provides in-home and office-based services to adults with developmental disabilities, director of a foster care agency, director of an outpatient drug treatment facility, and counseling in a private practice setting.

Amber specializes in severe and persistent psychiatric disorders, both in adults and children. Her professional goal is to provide the best caliber of services possible through education, supervision and support. She likes to think outside the box, provide new solutions to persistent problems, and help others feel appreciated and confident on a daily basis.

Muppet’s Mom Is Addicted

Mother’s Opioid Addiction Is Challenge for Newest Sesame Street Character

With deaths from opioid overdose rising to epidemic proportions, Sesame Workshop (the non-profit educational organization behind Sesame Street) recently introduced a new Muppet whose mother is battling addiction. The fuzzy green puppet with yellow hair named Karli debuted this May, but her storyline was expanded in October to include the fact that she is in foster care because her mother is in treatment for opioid addiction.

“Having a parent battling addiction can be one of the most isolating and stressful situations young children and their families face,” said Sherrie Westin, president of social impact and philanthropy at Sesame Workshop. “Sesame Street has always been a source of comfort to children during the toughest of times, and our new resources are designed to break down the stigma of parental addiction and help families build hope for the future.”

Over the five decades Sesame Street has been on the air, the show has not been afraid to tackle tough issues, creating one puppet who was homeless and another with autism. Sesame Street creators were motivated to incorporate this new storyline because 5.7 million children under age 11 live in households with a parent who has a substance use disorder.

The non-profit chose to incorporate Karli in its online resources rather than on its broadcast in order to give adult caregivers more choice over how and when they introduce the topic to youngsters. Sesame Workshop created the videos and articles because other non-profit partners were asking for more resources dealing with substance abuse.

Parental drug addiction is the second most common form of recurring trauma for children, after neglect, according to Christy Tirrell-Corbin, executive director of the Center for Early Childhood Education and Intervention at the University of Maryland. Tirrell-Corbin said, “There’s far too many children who are experiencing adverse events, this being one of them, to let this go unaddressed.”

Jerry Moe, the national director of the Hazelden Betty Ford Children’s Program, agrees. As a child therapist, he helped Sesame Workshop develop their resources for the pre-school age group. “These boys and girls are the first to get hurt and, unfortunately, the last to get help,” Moe said. “For them to see Karli and learn that it’s not their fault and this stuff is hard to talk about and it’s OK to have these feelings, that’s important. And that there’s hope.”